It’s early in the morning and John Vallez and Sophie Levi wander close to the shores of Lake Superior. A crisp breeze blows as waves gently crash against the rock. Vallez is a graduate student and Levi is working on her bachelor’s degree, and both are investigating extremely rare plants. Called arctic relicts, the plants only grow in a few areas in the entire world, two are the shores of Lake Superior and much farther north in the Canadian arctic.

Vallez and Levi are nimble on the smooth granite expanses, an area that 12,000 years ago was covered by retreating glacial ice. Levi kneels to examine a plant growing in a rock crevice. It’s Butterwort, Pinguicula vulgaris, and Vallez explains how the plant survives the harsh conditions. “It’s an insectivore,” she says. “It traps small insects on its sticky leaves.” The Butterwort needs supplemental nutrients because the habitat in which it lives is usually so nutrient poor.

Due to rising climate temperatures, the normally chilly lake water is becoming warmer. “The near freezing lake water creates the only place these plants can grow, it forms a unique micro-environment.” says Vallez.

In 2020, Lake Superior was strongly impacted by the heat. “It was two or three degrees above average.”The Research

Vallez and Levi are working with Briana Gross (an associate professor in the biology department) and Julie Etterson (a professor in the biology department), to determine how the plants will fare as Lake Superior warms. The plants are facing local extinction if they are unable to adapt.

Gross has been interested in these uncommon plants for years. Her research began in 2015 with a grant, “Genetics of threatened arctic plants,” which was funded by the Minnesota Lake Superior Coastal Program (MLSCP). University of Minnesota Ph.D. candidate Katherine Zlonis joined Gross in the research. In 2016 Gross and Zlonis worked with Etterson on a second MLSCP grant, “Coastal arctic plants and climate change.” Vallez and Levi are currently continuing the research on these arctic relict plants as part of a third grant to Gross and Etterson, this one from the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources.

There’s a total of twelve of these rarities in Minnesota, but Vallez and Levi are focusing on three: Euphrasia hudsoniana (Hudson Bay Eyebright), Pinguicula vulgaris (Butterwort), and Primula mistassinica (Bird's-eye Primrose).

Propagation

Vallez, who was a high school science teacher, is currently working on his master’s degree in biology. He’s not just studying the rare plants in the wild, he’s also in the lab.

“We tried to recreate the environment needed for the Hudson Bay Eyebright,” he recalled. “Out of 1,200 seeds that we tried to germinate, none of them took. None!” They tried everything they could think of to recreate the optimal conditions. “We tried freezing and thawing cycles, using various temperatures, and we even used a special germination acid.” No matter what method they tried, they couldn’t recreate the “environmental cues” needed to grow the plants.

Euphrasia hudsoniana (Hudson Bay Eyebright), Pinguicula vulgaris (Butterwort), Primula mistassinica (Bird's-eye Primrose)

Field Study and Genetics

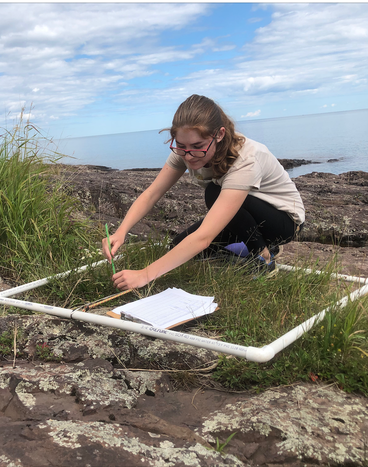

Levi is conducting her field and lab work as a full-time lab technician after completing an Undergraduate Research Opportunities Project in 2019. In the summer of 2020, she traveled with Vallez twice a week to sites on the North Shore of Lake Superior between Two Harbors and Grand Marais. Levi brings equipment to measure the growth and positions of the plants. Each week, at each site, she measures the progress of the plants in a carefully laid out square section. She makes notes about blooming, flowering, fruit, and any changes detected. She collects tiny samples to study and use for genetic analysis in the future.

“Just being able to do this research as an undergrad is crazy,” she says. She appreciates the beauty she gets to experience, “It’s amazing that I'm traveling and going out along the North Shore and seeing these rare plants.”

Next Steps

Gross and her team are now concentrating on learning how to protect the species for the future.

There is a lot to consider. Increasing tourist traffic is destroying some of the specimens. In addition, the team can tell from the genetic tests that some of the plants are hybridizing with invasive species. The research is also showing fewer plants in the southern study area.

Levi realizes the importance of the work and her role. “It will be so cool if I could possibly make a positive impact.

Banner photo above: John Vallez and Sophie Levi

About Swenson College of Science and Engineering

About the Biology Department