Kathryn Milun’s face brightens as she talks about the program. “This is an amazing, beautiful project,” she says. “It’s so much more than solar panels on top of buildings.”

Kathryn, an associate professor in the UMD Department of Anthropology, Sociology & Criminology, is referring to the partnership she helped establish in Tucson, Ariz., where a community organization in one part of the city is sending its electric bill savings from donated solar panels to another part of the city to fund a low-income community development program.

Suddenly, the benefits of solar energy include not only clean air and electric bill savings but also community empowerment. Now that project is in the running for a clean energy, “Solar In Your Community” award from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Solar Energy Technologies Office. The DOE will distribute $5 million in all.

When Kathryn talks about the Tucson project, she traces her fingers over a drawing of a mural which will go on a large wall in the neighborhood.

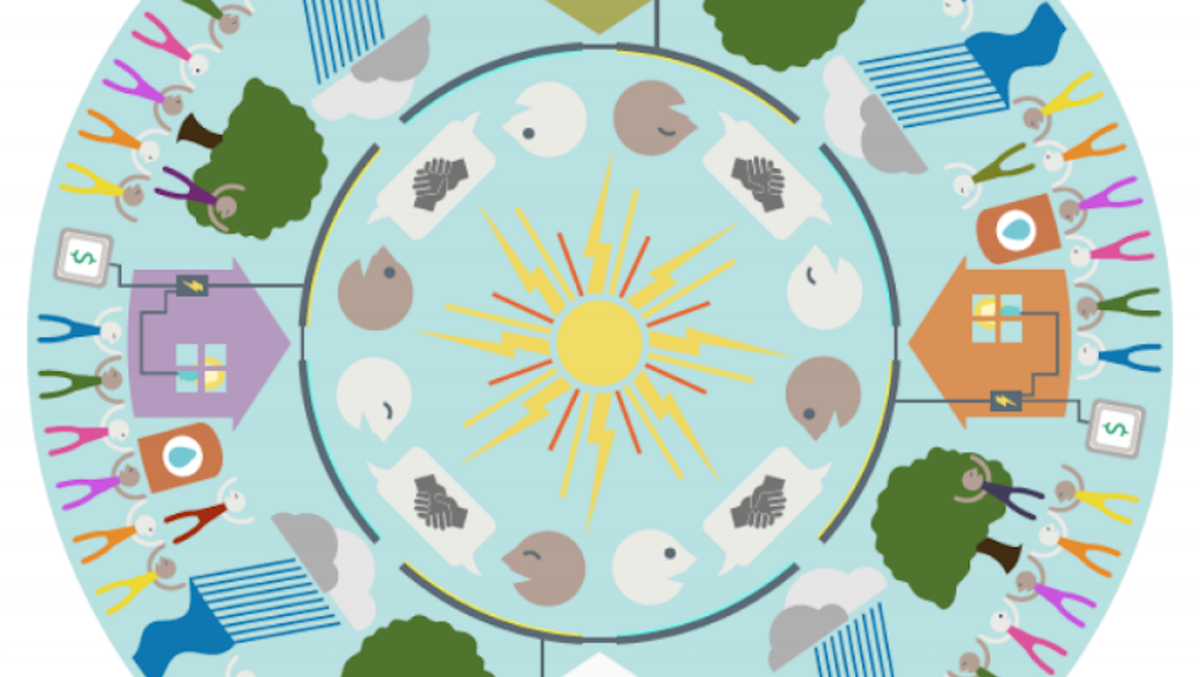

The circular mural, which will be painted over the 2019 summer, started from drawings done by neighborhood children. College students from the University of Arizona brought the children’s art together to create both a board game and a mural to show how this new model of community trust-owned solar works.

In the image, the sun stands fittingly in the center. Around the edges are houses, trees and gardens. Symbols for conversation, handshakes, money, water harvesting, and edible gardens, all tell how to capture and distribute solar energy benefits to those most in need. “Public art, on display for everyone to see, acts as the public face of this solar energy agreement,” Kathryn says. “It is truly community-owned solar.”

A Solar Commons

The project is called a Solar Commons, and it's based on legal ideas going back to medieval England when kings and barons owned all the land but “commoners” had rights to access and harvest what they needed for their own well-being.

As Kathryn, an anthropologist and affiliate faculty of the University of Minnesota Law School, explains, ”A Solar Commons makes sure low-income communities today can access modern, utility-owned electric grids to gather their fair share of the commonwealth benefits.”

The DOE initiated the ‘Solar In Your Community Challenge’ to serve low-income communities. The competition was designed to demonstrate new ways to make the electric grid more equitable. Kathryn’s Solar Commons project aims to do just that.

Kathryn has been developing the Solar Commons model for the past ten years. The Tucson project is the first existing Solar Commons prototype. Built in 2018, it began with a gift of 14.5 kW solar panels on the roof of the Dunbar School community center. Dunbar signed a Solar Commons Trust Agreement which Kathryn helped design along with her legal team and the Vermont Law School Energy Clinic.

Following the trust agreement, a local community development finance institution delivers the money that the Dunbar School saves on its electricity bill to the trust’s beneficiary, the Tucson Urban League’s low-income household weatherization and energy assistance programs.

As an anthropologist who studies social systems and cultural values, she knows that people need to look beyond the technology and money saved to appreciate the true value of solar. Kathryn feels strongly that public art can depict "the relationships between energy infrastructure, climate change, and income-inequality.” Making public art part of a Solar Commons "can show how our energy systems are connected to our earth systems and our social values," Kathryn says.

Duluth, Minnesota, and India

In Duluth, UMD students learn about the Solar Commons and other endeavors in Kathryn’s Energy, Culture, Society class. Since 2016, they have produced the Duluth Power Dialog, a public event that brings students together with community members and city leaders. The event examines local economic challenges and solutions facing the northland community on their predominantly fossil-fueled electricity grid. Students in Kathryn’s class also get involved and stay apprised of Kathryn’s current projects in Minneapolis and India.

In Minneapolis, Minn. Kathryn is working with Greenway Solar’s community “solar garden” project, a large-scale solar installation that allows low-income individuals, churches and nonprofits to obtain their energy from solar even if they are not nearby. The project includes a Solar Commons trust to provide paid internships for high school students to work with their community newspaper to report on local environmental justice issues.

Kathryn has also begun working on a third community solar research project. This one is in India and she is joined by UMD’s Devaleena Das, assistant professor of Women, Gender and Sexuality, and faculty members from the University of Arizona and the University of Calcutta. This project addresses issues of women’s economic empowerment through the use of solar-powered charkha (wheels) created to assist rural women in making a living by selling traditionally woven fabrics. Kathryn and Devaleena were recently awarded financing for the planning meeting from the University of Minnesota Institute on the Environment Mini-Grant.

Bringing Solar Projects to Communities

The projects don’t stop. In addition to her Minneapolis, Calcutta, and other projects, Kathryn is working on a book aimed at the general public called, Trusting the Sun. It tells the story of the Solar Commons in ways that connect environmental and social justice to the Do-It-Yourself community ethic of distributed solar energy.

“I’m excited about the shift in my research work to a community-engaged framework,” Kathryn says. She envisions Solar Commons projects in cities and towns across the U.S. which will provide access to the sun’s commonwealth benefits much like Carnegie Libraries provided access to books and knowledge a hundred years ago.

“Art and culture have to be a part of this community solar project, it’s not just about the hardware. Culture matters. People need to feel and care about the system that gives them energy.”

For more information, read the Solar Commons Model Financial Analysis and the Scalability Potential Study produced by the Rocky Mountain Institute in 2018.

Learn more about UMD's Anthropology Program.