The year was 1965. Boxes were stacked high around Bill Maupins. Hundreds of items, including furniture, clothing, food, and school supplies, filled the loading area. Volunteers worked alongside Maupins, arranging the items in the back of a semi-trailer. The shipment was on its way to deliver goods from Duluth to civil rights workers in Mississippi.

Maupins was the Duluth NAACP president from 1958 to 1969 and he worked at UMD from 1951 to 1982. This 1965 mission, to send support to the people in Mississippi who were fighting for voting rights, involved both his NAACP and his UMD roles.

Maupins encouraged UMD faculty, staff and students to make donations. He also rallied the NAACP community, the congregation at Duluth’s Temple Israel, and other organizations to join in. They filled the entire truck.

The trip was more complex and more dangerous than a simple delivery. In the early 1960s, hundreds of people who dared to fight for civil rights for African Americans had been killed by the KKK. Violence in Mississippi was reported on the news every day.

In spite of the danger, UMD Chaplain Brooks Anderson, a friend of Maupins, was compelled to help the civil rights movement in Mississippi. Anderson and several UMD students, including Deanna Johnson, Orlis Fossum, Darlene Keeler and Kenner Christensen, elected to follow the truck to Jackson, Mississippi. There, they heard about the now-historic march from Selma to Montgomery. That took them another 200 miles, where they joined Martin Luther King, Jr. and many national leaders on the march.

Born in Duluth

Maupins’ story starts in a hotel in Duluth, where Maupins was abandoned as a baby in 1922. He was taken in by a young woman, who died a short time later. Maupins was then adopted from an orphanage by a married couple. His adopted father was an elevator operator and shoe shiner at the Duluth Hotel.

Maupins went on to attend Central High School. After graduation, he served in the United States Navy during WWII and later went to UMD. Just three years later, in 1951, Maupins was a college graduate with a degree in political science.

Service to UMD

After graduating from UMD, Maupins began work as a janitor on campus. This didn’t last long though, because Maupins’ drive and intelligence were recognized. He soon landed in the position of chemistry laboratory supervisor. In the 1950s, the faculty and staff were so impressed by Maupins that Provost Ray Darland added affirmative action duties to Maupins’ role. Duluth activist Claudie Washington says, “Bill noticed young people with promise and made recommendations to the UMD administration. I personally know over 40 people who were hired at UMD because Bill Maupins spoke for them.”

The Life of an Activist

During his early years as a UMD student and employee, Maupins saw injustices taking place against African Americans and others. He felt he had a duty to speak out and take action.

“Many avenues are closed to Negroes,” Maupins said in a Statesman article in 1947. "For one who seeks to prove his status on the basis of his college preparation, the opportunities are limited.”

In 1958, Maupins ran for a position with the Duluth NAACP on the platform of fair education, housing, and employment for African Americans. He won, and in 1963, he became the NAACP president. This provided Maupins with a platform to do groundbreaking work as a civil rights leader.

Fighting Discrimination

Maupins and the NAACP were active in voter registration. They launched several initiatives, including one that helped to register nearly 100 African American voters in 1964.

He worked with the State NAACP to make recommendations for a state fair housing ordinance and to fight for the eventual national Fair Housing Act of 1968. In Duluth African American renters and buyers faced wide-spread discrimination in housing. The NAACP files are full of deplorable incidents. One occurred when a young African American man was cheated out of his apartment rental and deposit after the landlord found out the man was an African American. Without a housing ordinance, renters had no recourse.

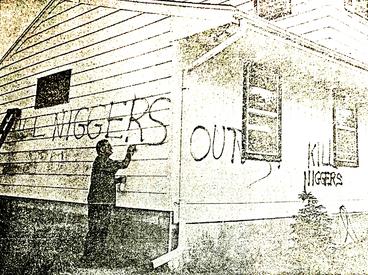

Another was the hateful vandalism of an African American family’s home in the Lakeside neighborhood of Duluth. Racial slurs were spray painted on all sides of the house. Even the sidewalk was covered.

Inspiration for Many

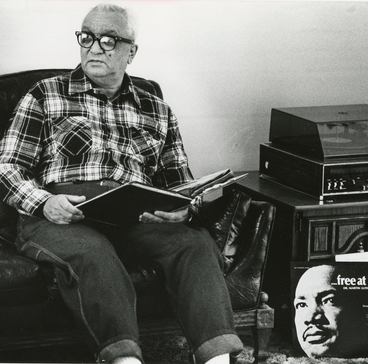

In his later years, people often visited Maupins in his home. Portia Johnson, a member of the ISD 709 Desegregation/Integration Council, and a City of Duluth civil servant commissioner, would stop by often. “Bill would sit in his favorite rocking chair and listen to our struggles on affirmative action. He was always good at working out strategies.”

Maupins passed away in 1992, but he left a legacy of positive change. His influence is still felt by people in the city of Duluth and at UMD.

Top banner photo: William Maupins in a UMD chemistry laboratory.

This story was written by UMD student Izabel Johnson, who is majoring in journalism and minoring in communication. Izabel works with Cheryl Reitan in University Marketing and Public Relatons

Support Diversity at UMD

See more information about the William Maupins Memorial Scholarship and other scholarships and funds that assist underrepresented students and faculty at UMD.

___

SEE MORE