Archie J. Vomachka was a biology student at UMD in the late 1960s and he has vivid memories of an unusual research project at UMD. One of his professors, Theron O. Odlaug, received funding for a three-year baseline study of plankton in Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, and Lake Huron.

Somehow, Odlaug had made arrangements with the United States Steel's Pittsburgh Steamship Company and the Hanna Furnace Corporation Steamship Company to allow UMD to drag equipment behind ore carriers on 45 voyages, during three summers: 1967, 1968, and 1969.

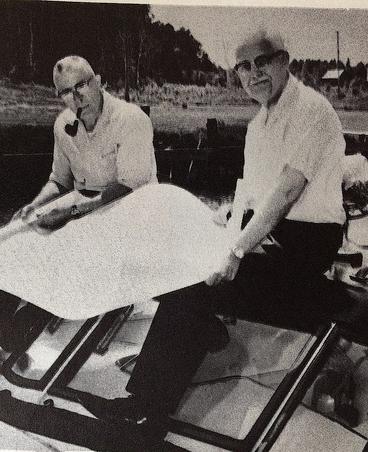

It was a tremendous adventure for the college students. Archie, his brother, Jon Vomachka, and others, collected plankton data on the long voyages. Their friend and classmate, Ed Bersu stayed dockside to analyze the samples. They all remember joining the ore boat crew to load the massive CPR (continuous plankton recorder) up on the deck and then mount it to the back of the ship.

On Board

Archie recalls a fateful trip. “We were coming back to Duluth, when we heard a huge boom,” he says. “The carrier kept plowing along, but we knew something was wrong.” When they got to the back of the ship, they could see that the stainless steel cable had snapped. “I can’t imagine what the recorder caught on, but it had to be massive and heavy.”

(L-R) Lowering the plankton recorder into the lake, UMD alumni Archie Vomachka '68, Jon Vomachka '71, and Edward Bersu '68.

Jon recalls a similar mishap, but the consequences were more severe. His team lost a plankton recorder too, but at the beginning of the trip, before any specimens had been gathered.

“We left Taconite Harbor in the middle of the night,” Jon says. “Two of us were lowering the recorder into the water and the winch suddenly jammed. The winch was half the size of a refrigerator with a crank on each side.” Jon and his partner thought the brake shoe was stuck so they hammered on it in order to break it free. They were successful in loosening it, too successful. “We heard the recorder going all the way down, 1000 feet, to the bottom of the lake.”

Twice, Archie travelled on the Cason J. Callaway across Lake Superior, through the Soo Locks, at Sault Ste Marie, into Lake Michigan and back. Once the ship stopped in Gary and the other time in Hammond, Indiana. Jon went on too many trips to count. He went out every year for the three years of the study. He traveled on Lake Superior, Michigan, and Huron, for the study and even went to Lake Erie, when the ship had an extra stop to make.

The students were treated well. “We ate meals at the captain’s table, and spent a fair amount of time in the wheelhouse,” Archie says. Day and night they collected samples, pulling in specimens caught in the fine silk screen mesh inside the plankton recorder.

Back in Minnesota

Ed Bersu traveled to the ore boats with other students and assistants, but he never took a long voyage. He remembers going to the Cason J. Callaway. “I was with Mike Adess, UM-Twin Cities doctoral student, and we had to get the plankton recorder to the dock in Two Harbors.” There were other students from the University of Minnesota School of Public Health doing plankton research for Odlaug’s study: William Parkos, Robert Nelson, and Art Charbonneau.

Most of the time, Ed joined other student workers to analyze the data back in the Limnology Lab. The 45 voyages yielded a great amount of plankton life to be recorded.

Odlaug’s research study set out to do something never done before. They were the first to demonstrate the usefulness of the continuous plankton recorder to a freshwater research program. They also obtained baseline information about water quality based on an analysis of zooplankton occurrence and distribution in the Great Lakes.

How It Started

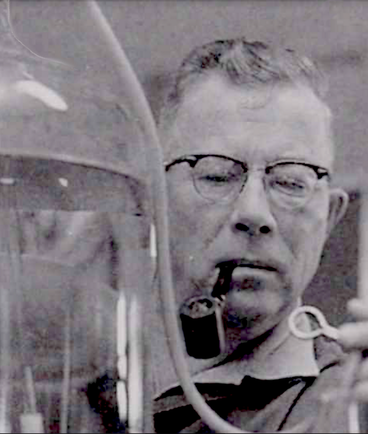

Beginning in the mid-50’s, Odlaug, UMD professor of biology, was the co-director of a University of Minnesota program that provided training and research experience in aquatic biology for teachers, graduate students and public health personnel. Odlaug, who studied zooplankton, set up the UMD Limnological Research Center on London Road.

In the early 1960s the research vessels, the Oneota, an older wood-hulled boat and the SS Jacobs, a newer steel-hulled vessel were used for research. They were docked at Knife River, Minnesota. Jon remembers helping graduate students conduct summer research studies by diving off the boats for samples.

The Ecology of the Second Trophic Levels Study

The Great Lakes plankton study started In 1966, when Odlaug’s program received funding to purchase four CPRs (continuous plankton recorders), at that time, a novel sampling device. He enlisted the steamship companies, collaborated with other universities, set up a research lab, and hired students.

Three ore carriers hosted the scientists, the S.S. Cason J. Callaway, S.S. Sewell Avery, and the S.S. Ernest T. Weir. Odlaug appreciated the seamen. He publicly thanked the crews, “for their willing hand at the winch and the long periods of ‘yarning’ in the blacked-out wheelhouse, which made the long nights easier.”

The teams collected a continuous record of the microscopic plants and animals in three of the Great Lakes from 1965-1969. Odlaug, along with Theodore A. Olson and Wayland R. Swain, compiled their findings in a 1970 study, “The ecology of the second trophic levels in Lake Superior, Michigan and Huron.”

The Impact on the Students

Archie Vomachka, Edward Bersu, and Jon Vomachka, the UMD students who worked with Dr. Odlaug on the plankton study, speak highly of the experience. The positive environment in the lab and the support of the professors made a lasting impression on the students. Jon says, “It was a formative experience; it changed my life.” When he first started working on the project, he was more enamored with carpentry than academia. That changed as he was able to merge his (by all accounts) remarkable mechanical skill with Dr. Odlaug’s research requirements. Jon received his bachelors and masters degree in biology at UMD and went on to teach public school science for 13 years and serve as a principal for 21 years.

Archie’s success was stellar as well. From the Ph.D. in Zoology at Michigan State all the way to founding dean of the College of Health Sciences at Arcadia University, in Pennsylvania, Archie’s accomplishments didn’t stop. He has dozens of publications and scores of scholarships, awards, honors, and grants to his name. And still, after all these decades, he remembers Dr. Odlaug for inspiring a career in the life sciences.

Ed’s accomplishments speak for themselves: Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and a position as an expert on gross human anatomy and anatomical variations, as well as human embryology for the University of Wisconsin-Madison Medical School. Ed, too recalls Dr. Odlaug. “I remember thinking, if I could be as good of a teacher as any of my professors at UMD, I would be a success.”

Banner photo, top of page: Archie Vomachka on the S.S. Cason J. Callaway at the Mackinac Bridge.

About the Department of Biology

___

SEE MORE